Land Stewardship in Flash Flood Alley

Habitat Enhancing Land Management

“Walking the land and observing the destruction requires disengagement from emotions and memory; I simply need to breathe and accept the reality. I begin to reexamine responsibilities of stewardship for this small piece of the earth I call home.”

—Roger Colombik, Wimberley sculptor impacted by the 2015 Blanco Flood

Christine Middleton

Extreme floods are not new to Central Texas. One only needs to observe the deep canyons to understand that major flooding has been part of the Texas Hill Country for eons. The first historical record of a major flood took place in 1819, at a time when San Antonio was the largest Spanish settlement in Texas. Since then, Central Texans have experienced numerous floods, some of which resulted in damaged property and lost lives. Those who have lived in Hays County for a long time remember the flood of 1998 that inundated San Marcos. Many more of us witnessed the 2015 “Memorial Day Flood” that swept down the Blanco. More recently, the devastating flood that took place in the Kerrville area this past July 4th took our collective breath away.

The USGS defines two types of inland floods: river flooding and flash floods. River flooding generally impacts larger rivers located in areas with wetter climates than Central Texas. Long-lasting rains (and sometimes melting snow) mean excess runoff causes those rivers to rise slowly. The result is lots of property damage, but most people have time to get out of the way or be rescued.

Flash flooding is more common in areas like the Texas Hill Country, characterized by steep slopes and shallow soils. Torrential rains mean water flows rapidly overland rather than soaking in as it would during less intense storms. The result: rapidly rising, fast-moving water that comes with little warning. Trees and other vegetation are swept away as the water picks up steam. Houses are flooded and sometimes destroyed. And tragically, people don’t always have time to get out, and fast-flowing waters stymie rescue efforts.

Caption: Home in Wimberley damaged by the 2015 Memorial Day Flood

Flooding and the danger it presents depend on a number of interrelated factors. First, there is the geology—not just steep slopes, but also what they consist of and how much soil lies on top. Then there is the amount, duration, and location of the rain. And we humans often make matters worse by actions that inadvertently encourage the rapid flow. Development in the form of roads, houses, and other impermeable cover is part of the problem. So too are land practices that increase the speed with which runoff reaches the Hill Country’s numerous creeks and rivers.

Geology + Climate + Vegetation

“Since the border region of the plateau is very rough and highly dissected, the water will flow off after heavy rain before it has time to enter the limestone formation; and with such volume and velocity as to cause swift and destructive floods, unless detained by some agency other than the limestone structure of steep hillsides. That is exactly the function which a timber or heavy grass covering performs.”

— William L. Bray, University of Texas-Austin forest ecologist

So what makes Central Texas so flood-prone that it has long been dubbed “Flash Flood Alley?” The above quote from William L. Bray’s 1904 publication Timbers of the Edwards Plateau of Texas: Its Relation to Climate, Water Supply, and Soil captures the three factors that influence the intensity of floods: geology, climate, and vegetation. But, specifically, what is it about these three factors that make Central Texas more vulnerable to fast-moving, often deadly floods than many other places? And how might changing weather patterns and increased Hill Country development affect the precariousness of our situation?

Caption: One of the many creeks found on Hays County properties HELM visits

It all starts with the geology—specifically the fact that much of the Hill Country is, as the name implies, hilly. Those slopes are primarily limestone covered by thin soils. But that’s not the whole story. We live in a high-drainage area, meaning there are lots of channels in relation to the area being drained. As rainfall hits the ground, water naturally flows downhill. In a light rain, the rainwater may simply soak in. But in a heavy rain, especially if the ground is already saturated, the water runs off.

Mel Sieb is redrawing this diagram - if don’t get in time simply eliminate

Given thin soils, it doesn’t take a lot of rain for the ground to reach saturation. As the rain continues, the runoff quickly reaches one of the many existing channels, be it a gully, a seasonal or perennial creek, or a river. Gravity moves the water downhill, and the steeper the slope the more speed is gained. As channels merge, the total volume and mass increase dramatically.

Increased weight and momentum make the water exponentially more powerful and destructive. The width of the channel can also influence the rate of flow. In the Blanco flood, the heavy rain that fell upstream in the Blanco area backed up when it reached a quarter-mile canyon with 40-foot walls appropriately called the Narrows. The water exited the canyon with sufficient force to take out the bridge at Fischer Store Road as it barreled toward the City of Wimberley.

Caption: Remains of Fischer Store Bridge following the 2015 Blanco flood

The manner in which the rain falls is as important as the sheer quantity. This past July 4th, 10–12 inches of rain fell west of Kerrville within just a few hours. The impact would have been very different if the same amount of rain had fallen over a period of several days. The numbers associated with the rate at which the water rose and picked up speed are staggering. At midnight, an hour before the rain started, a Guadalupe River gauge in the upper basin near Hunt registered 7 feet with a flow of 8 cubic feet per second. Just three hours after the rain began to fall, the level was 29.45 feet and the water was flowing at 120,000 cubic feet per second. That’s more than the rate at which water flows over Niagara Falls!

Where the rain falls is another significant factor. The rains that stalled over Kerr County involved a single watershed and fell primarily near the headwaters of the Guadalupe. The area is also upstream of the place where the North and South Forks of the Guadalupe River merge just north of the town of Hunt. As the water moved eastward, as with the Wimberley flood, it was funneled through a narrow area of hills and limestone cliffs before approaching Ingram and Kerrville.

And it was not just one storm over Kerr County. Rather, the area was hit by training thunderstorms. The meteorological term “training” is derived from the fact that the way such storms move is reminiscent of train cars passing over the same section of track. One storm drops a lot of rain and moves on, but the vacant space is quickly filled by another and then another, resulting in a tremendous amount of rain over the same area in a short period of time. The result can be a flash flood of breathtaking magnitude.

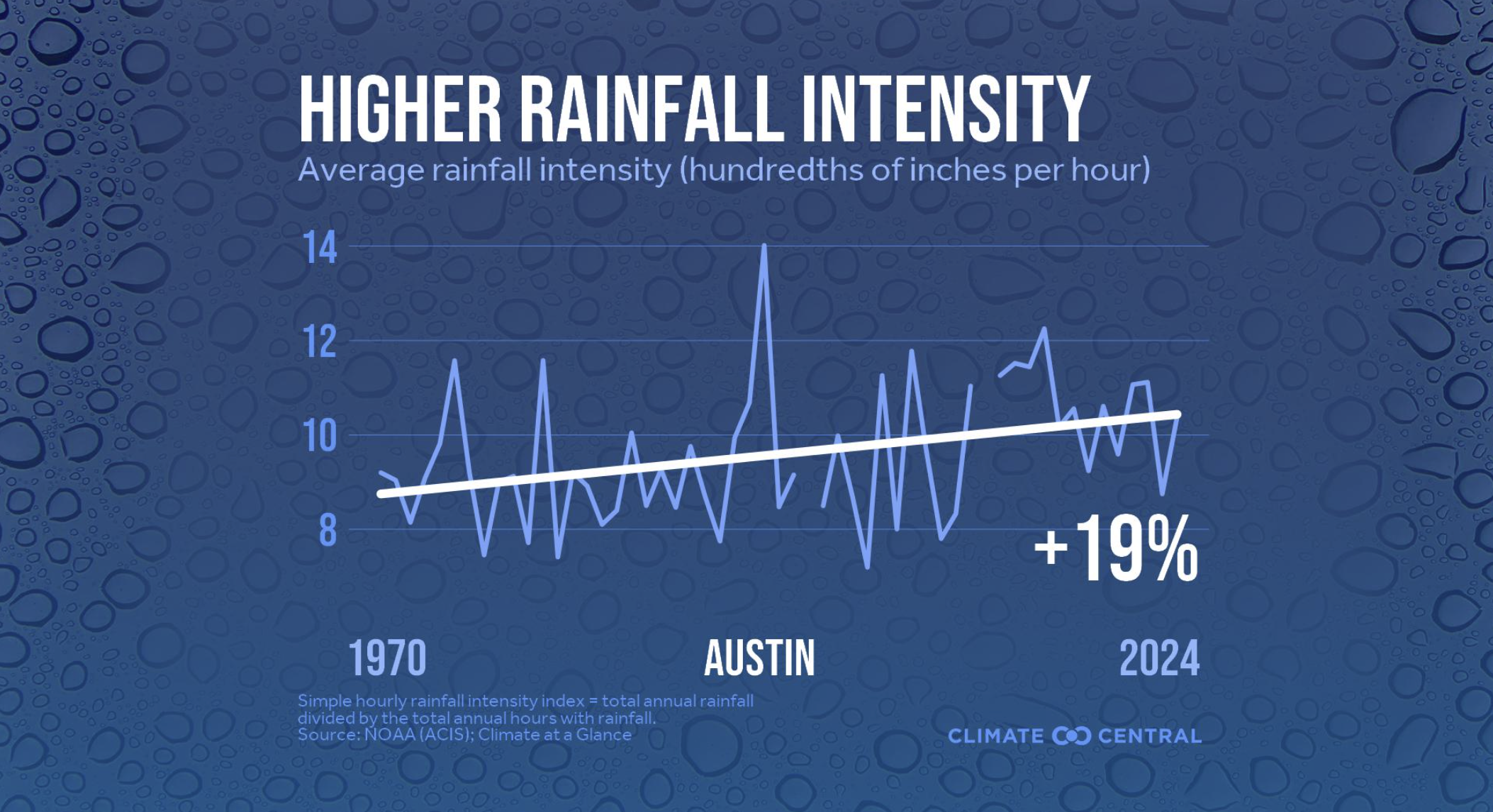

Changing weather patterns brought on by atmospheric warming are creating conditions for more heavy, localized rainstorms across the U.S. Warmer air translates to more moisture held in the atmosphere. Changes in the jet stream’s path and speed mean storms are more likely to stall in one place for longer periods. And greater atmospheric instability makes such storms harder to predict. While some parts of the country have experienced even greater percentage increases, nearby Austin’s 19% increase in average rainfall intensity (total annual rainfall divided by the total annual hours with rainfall) between 1970 and 2024 is definitely concerning.

Source: ClimateCentral.org

The third factor is vegetation—how much is growing between where the rain hits the ground and the nearest channel. In his 1904 report, Bray compared two gorges that drained to the Colorado: one had retained thick vegetation and the other had been stripped clean. Bray noted that “… after a violent downpour of rain, water rushes down the sides of bare, steep hills with a power which carries not only any remnants of soil, but the fragments of rock as well … whereas when the sides are heavily timbered, the organic debris drinks up and detains the water, so that not only is this heavy covering of leaf mold not washed away, but the water does not acquire the momentum and volume sufficient to sweep out the channel of the gorge itself.”

Caption: A page from William Bray’s report illustrating the two canyons he studied

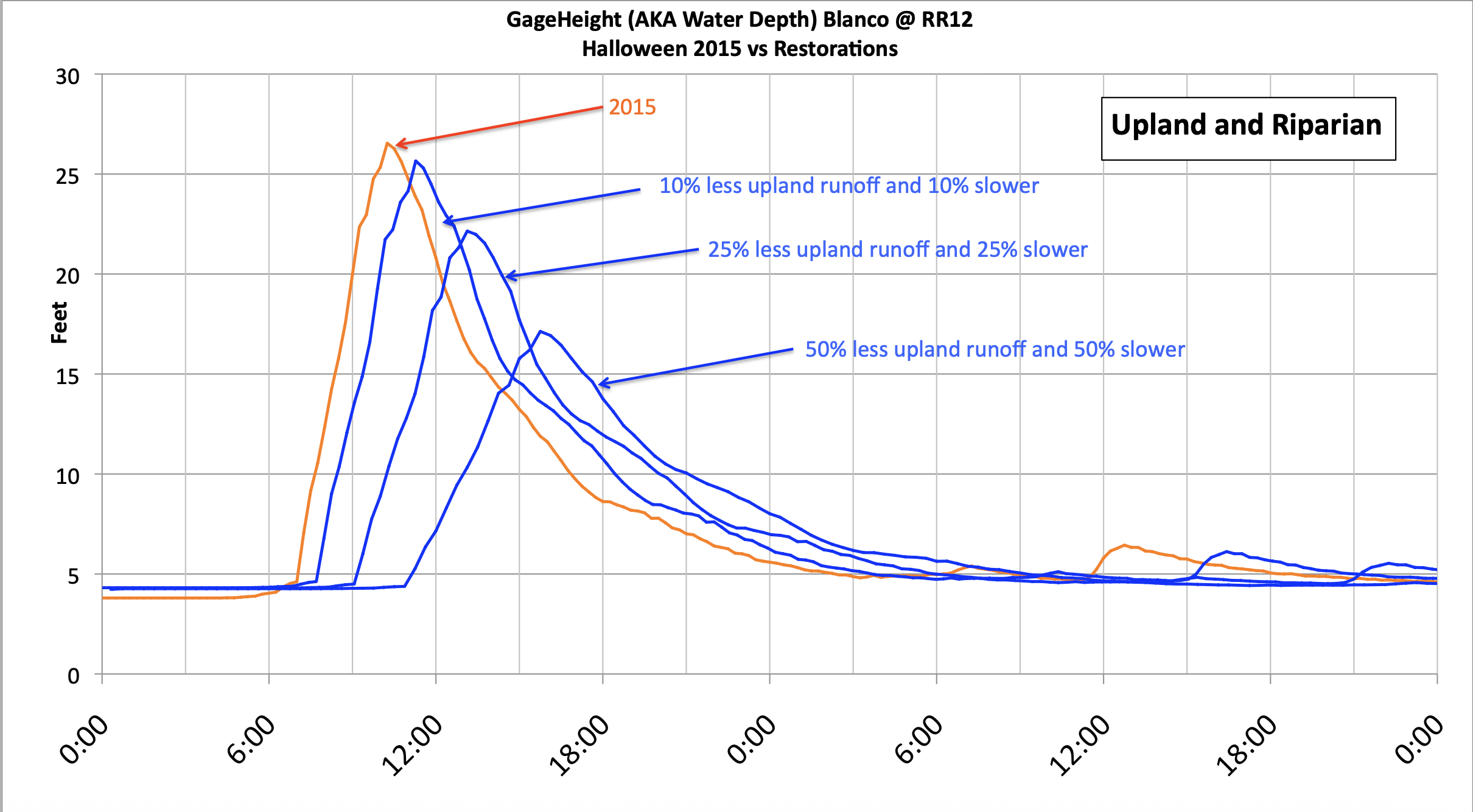

A theoretical study was done by Hays County Master Naturalist and retired geologist LaRay Geist. His calculations involved two major, but less devastating, floods that also impacted the Wimberley area. Both were in late October, one in 2013 and the other in 2015, and are thus referred to as the Halloween floods. LaRay described his work as “a very technical analysis … that would make most folks’ eyes glaze over.” Unfortunately, LaRay passed a few years ago and his study was never peer reviewed. But he left us with two graphs and a brief explanation.

The first graph superimposes the USGS gauge heights on the Blanco River at the RR12 bridge for the two Halloween flood events.

At that point on the river, a level of 17 feet is considered a moderate flood and 26 feet a major one. The graph illustrates how the water rose rapidly, from around 5 feet to 27 feet in just three hours, and then stayed above 20 feet for another three hours.

The key takeaway, according to LaRay, is “how quickly the river went from normal flow to flooding (i.e., flash flooding).”

LaRay then pondered what would happen if some of the rapid runoff had soaked in and the rest had been slowed down.

The second graph shows how the 2015 flood might have looked in three hypothetical scenarios. The scenarios assume landowners took steps to capture a percentage of rainfall, enabling some to soak in (10%, 20%, and 50%), and that a similar percentage of upland runoff took three more hours to reach the river.

The results suggest that slowing and sinking the water can reduce peak flows. LaRay observed that if landowner actions resulted in a 50% reduction and 50% delay, “… the 2015 Halloween ‘flooding’ would have been a non-event.”

At the RR12 bridge, the 2015 Memorial Day flood crested at just under 45 feet before the gauge was lost. Back then, riparian expert Steve Nelle suggested nothing could have stopped the catastrophic wall of water that washed down the Blanco, uprooting gigantic cypress trees and mowing down other vegetation. He voiced the same opinion recently after the July 4th flood, which had the same disastrous impact on vegetation. (That flood crested at 37.52 feet at Ingram, setting a new record for the Guadalupe River.)

While the effect of vegetation on runoff might be less pronounced in such catastrophic floods, further degradation of our landscape has the potential to turn moderate floods into major ones. With more heavy rains on the horizon, most experts agree we need to consider the impact of current land management practices on runoff rates and adjust such practices accordingly.

Flooding Starts at the Top of the Hill

So where should landowners conscious of the potential for future floods start? The first step is to simply develop a better understanding of how water flows across your property. Begin by understanding the topography of your land. Find a contour map if you don’t already have one. (The HELM team brings one with them for every property visit.) Each contour line represents how high that point is above sea level. The distance between contour lines provides an indication of steepness—the closer the lines are together, the steeper the slope.

Water generally flows downhill perpendicular to the contour lines. A shape reminiscent of an arrowhead indicates a place where water gathers and flows faster off the hillside. It could indicate a waterway with the arrow pointing upstream, or it could simply be a gully or seasonal creek that flows only when it rains. Also note where your house and other impermeable surfaces (e.g., road, driveway, barn) sit relative to the slope. Try to understand where the water goes after flowing off the impervious surfaces we humans have placed in the way.

Caption: Notice how water flows off canyon walls on this property.

Now go outside and walk your property. Start at the highest point and work your way down, following the path of water across your land. If you don’t mind getting a little wet, perform an “umbrella survey.” That is, go out when it is raining (but not thundering). It doesn’t have to be a heavy rain, just enough to observe the direction and velocity of the runoff. If you don’t own the top of the hill, start where runoff from your uphill neighbor enters your property.

Ask questions, such as:

Are there places where the runoff flows onto the property more rapidly than at other locations?

Is the flow picking up speed as it moves across the property?

What is happening at points where the water flows off a roof or driveway?

Are there places the runoff is beginning to channelize?

Or go out soon after the storm has passed, particularly if the rainfall was heavy enough to create lots of runoff. Reading the signs the water left behind can be invaluable in identifying places that need to be addressed before the next heavy rainfall. Look for areas where vegetation is scarce, particularly spots that have clearly begun to erode. Best to address erosion when it first starts, so look for places where small rivulets have begun to form. Or spots where leaves or cedar needles have clearly been displaced by the recent rain. Grass pushed over in one direction is also a good indicator. Overall, look for opportunities to slow down and spread the flow before it becomes channelized. For more on runoff and erosion, see the earlier HELM Network News: Don’t Go With the Flow in the July 2022 Hays Humm.

Caption: Key indicators of water flow—cedar debris (left) and downed grasses (right).

Land Management for Flood (and Drought) Mitigation

There is little landowners can do to change the geology under their property. Nor do they have control over how hard the rain falls on their land. But land management practices can influence how much of that rain soaks in and how fast the rest runs off. And, by fortunate coincidence, practices designed with flood mitigation in mind are also beneficial in times of prolonged drought!

Caption: Clear-cut hillside with little vegetation to slow runoff.

Experts may debate whether trees or grasses are better for water infiltration, but they clearly agree that vegetation is the answer—the more the better. Native vegetation anywhere is a good thing for a variety of reasons. In terms of flood mitigation, however, the vegetation on steep hillsides and in riparian areas is probably the most critical. Top growth slows the flow of runoff, giving the water more time to soak in, and strong roots protect the soil and prevent erosion.

On steep slopes, clear-cutting cedar leaves soil exposed, and the increased runoff makes it hard, if not impossible, for seeds to take hold. That means the hillside is likely to remain barren for years to come. If an area truly has too much cedar (and that can happen, as cedar is an aggressive native), go about dealing with it in a slow and methodical manner, taking out just a few trees at any given time. For more on the beneficial aspects of cedar and the implications for land management practices, see the earlier HELM Network News Rethinking Mountain Cedar in the June 2022 Hays Humm.

Mowing too much and too often can also impact the rate at which water crosses your property on its way to the nearest creek or river. And if you are lucky enough to have a creek or river bordering your property, mowing large swaths along the banks can be particularly detrimental. Think carefully about how much of your property you truly need to mow on a regular basis to protect your home from fire and provide just enough space for family recreation. On the rest of the property that is not heavily wooded, encourage tall native grasses. And those with waterfront property should maintain a healthy riparian buffer to protect the banks from future flood events.

Caption: Jackaroo demonstration illustrating how to encourage rapid revegetation after a flood.

That doesn’t mean you have to walk through tall grasses on your way to a viewpoint or place you like to enter the water. You can regularly mow paths and small access points that enable you to enjoy your favorite spots. The only piece of advice is to add enough curves so water is less likely to flow quickly down the path and cause erosion. The rest of the property only needs mowing, preferably in late February, every few years, if at all. For more on native grasses and mowing, see HELM Network News Appreciating Native Grassland, Part 2: Learning to Manage Them in the October 2023 Hays Humm.

When trees are damaged by an intense storm, whether the culprit is wind, ice, or flood, the first urge is to clean up. Definitely clean up around your house and driveway and along the paths you like to walk. Also remove any debris full of trash, invasive plants, or anything that presents a safety hazard. But consider leaving as much of the downed wood in place as possible. (An added bonus: fireflies need rotting wood and leaf litter to complete their life cycle!) You might move some branches to a spot appropriate for a brush pile. The birds will thank you for creating a safe place where they can forage for insects. And definitely use downed tree trunks and heavy branches for erosion control. For riparian landowners, remember that downed wood is particularly important for rebuilding riverbanks after a major flood.

Caption: Handout after the July 4th flood advising landowners on woody-debris management.

Landowners concerned with capturing more water on their land might want to investigate how to build water-harvesting earthworks. The Balcones Canyonlands Preserve has a project involving building a series of bioswales on a degraded hillside. Bioswales are shallow, sloping troughs placed on contour that rehydrate the hillside and reduce erosion by capturing, spreading, and sinking rainwater. This video provides more information on that project.

Caption: One of the bioswales that is part of the project at Balcones Canyonlands Preserve.

There are also lots of other ways to capture rainwater. A place you might want to visit is Headwaters at the Comal, where they have built a series of berms and swales designed to capture water before it reaches the Comal River. Although written for an even drier climate than our own (Arizona), a good reference for learning about a variety of possible approaches is Brad Lancaster’s Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond: Volume 2 — Water-Harvesting Earthworks.

Caption: One of several swales at Headwaters at the Comal after a recent rain.

Request a Fall HELM Visit

Want help figuring out how the water flows across your property, how to manage cedar, or how to revegetate your eroded hillside? Or have other concerns about how to better steward your property? As part of our HELM (Habitat Enhancing Land Management) program, we offer property visits to discuss land stewardship. Landowners learn about sustainable practices designed to enhance wildlife habitats, improve soil, effectively manage invasive species, and much more!

We still have room for a few more fall 2025 visits. If you or a neighbor would like a HELM team to visit, fill out this HELM visit request form. And please help us spread the word!

The HELM Network News is a periodic feature in The Hays Humm, the online magazine of the Hays County Chapter of the Texas Master Naturalist™. You can read the latest issue and explore past articles at this link.