What Good Is It?

Part 2 - Habitat Enhancing Land Management

Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

“In nature, nothing is perfect and everything is perfect. Trees can be contorted, bent in weird ways, and they’re still beautiful.” —Alice Walker, American novelist, poet, and social activist

Christine Middleton

What Good Is It? – Part 1 discussed plants, mostly natives, that hurt or otherwise annoy us. Disliking such species is understandable. But when looked at from a different perspective, all had ecological value—sometimes in surprising ways.

Part 2 examines plants people denigrate because they can become a bit too aggressive for our liking. Often the offending plant is called a weed and then completely obliterated wherever it grows. But the term "weed" has no biologically based definition. The label simply implies that someone, at some time, decided that particular species was worthless.

As Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, “What is a weed? A plant whose virtues have never been discovered.”

Native species that sometimes get out of hand are frequently labeled invasive. But to be officially considered “invasive,” the offending plant must be both non-native and in some way harmful to the environment, economy, or human health. Another term, “native invasive,” pops up at times. But that too implies the plant is totally undesirable. "Aggressive native" more accurately describes the situation. That term implies the plant evolved ways that make it highly successful in situations where other natives fail to thrive. Combine these survival strategies with other factors—sometimes natural, other times human-caused—and conditions are ripe for awarding that species an outsized competitive advantage.

So, don’t automatically demonize any Texas native because it sometimes misbehaves. Instead, learn more about that particular species. Ask: What ecological function does that species provide? Does it hold, build, or improve soil? Whom does it feed, and at what time of year? Does it provide shelter from predators or winter winds?

And don’t automatically blame the plant for its bad behavior. Ask what has happened, or is happening, at the site where it is growing that might account for the absence of other species competing for the same space. Then use that knowledge to formulate a management plan for that species based on restoring balance—not annihilation.

Prairie Tea—Just Doing Its Job

Prairie Tea (Croton monanthogynus) is a good example of a native species that has acquired a reputation for looking weedy and is sometimes mistakenly targeted for obliteration. Prairie Tea is also referred to as One-seed Croton, Doveweed, and Prairie Goatweed. As with many plants, common names tell you something about the plant. Some say Prairie Tea can be used to make tea, while others warn against it due to concerns about toxicity.

Prairie Tea (Croton monanthogynus) Photo courtesy Christine Middleton

Photo courtesy Christine Middleton

One-seed Croton refers to the fact that, unlike many other crotons, its fruit contains only one seed. Doves consume those seeds, which explains the third name. And goats are about the only herbivores who will eat the foliage.

Prairie Tea is just one among many native species that thrive in disturbed areas. A disturbed area can be naturally caused—fire, flood, drought, etc.—or we humans and our machines can be the culprits. Rather than calling them “annual weeds,” a better way to think about such plants is as pioneer species. Pioneer species have evolved to survive under harsh conditions where other natives might struggle—little or no soil, limited microbial activity, etc. These species are usually fast-growing and produce lots of seeds, enabling them to quickly populate a recently disturbed plot of land and stem erosion. Their seed dispersal strategies use wind, animals, or other techniques that allow them to get there first.

Artistic rendering courtesy Melinda Seib

Pioneer species are the first step in the successional process. They help build soil and keep it in place. Many such species alter the soil in ways that make it more favorable for later arrivals, as discussed in a recent article—It’s All Connected Underground Too!

Also, by taking up space, these hardy pioneers defend the area from invasives that often gravitate toward disturbance.

One aspect of Prairie Tea that can accentuate its tendency to dominate is the fact that, unlike certain other early succession annuals, Prairie Tea is highly deer-resistant. Even cattle tend to ignore it except during times of drought.

Admittedly, Prairie Tea is not the most attractive of our native species. But its seeds provide sustenance not just for doves but also for other birds. In fact, birds are the primary distributors of its seeds. The plant’s delicate white flowers are inconspicuous, and there is not much information on who pollinates them—most likely small bees, flies, and/or wasps.

What we do know is that Prairie Tea is the host plant for the Goatweed Leafwing butterfly, whose caterpillars relish chomping down on its leaves. Beyond its value for wildlife, the roots of Prairie Tea are important in creating conditions amenable to later succession species. This tap-rooted annual is very effective at holding soil in place, and its roots are strong enough to crack open compacted soil. Then, as the area recovers and succession begins to bring in taller species, Prairie Tea will gradually die out.

That can be a slow process—and we humans are impatient. However, rather than eliminating Prairie Tea, consider simply jumpstarting the next successional stage by gradually introducing later succession perennial grasses and wildflowers.

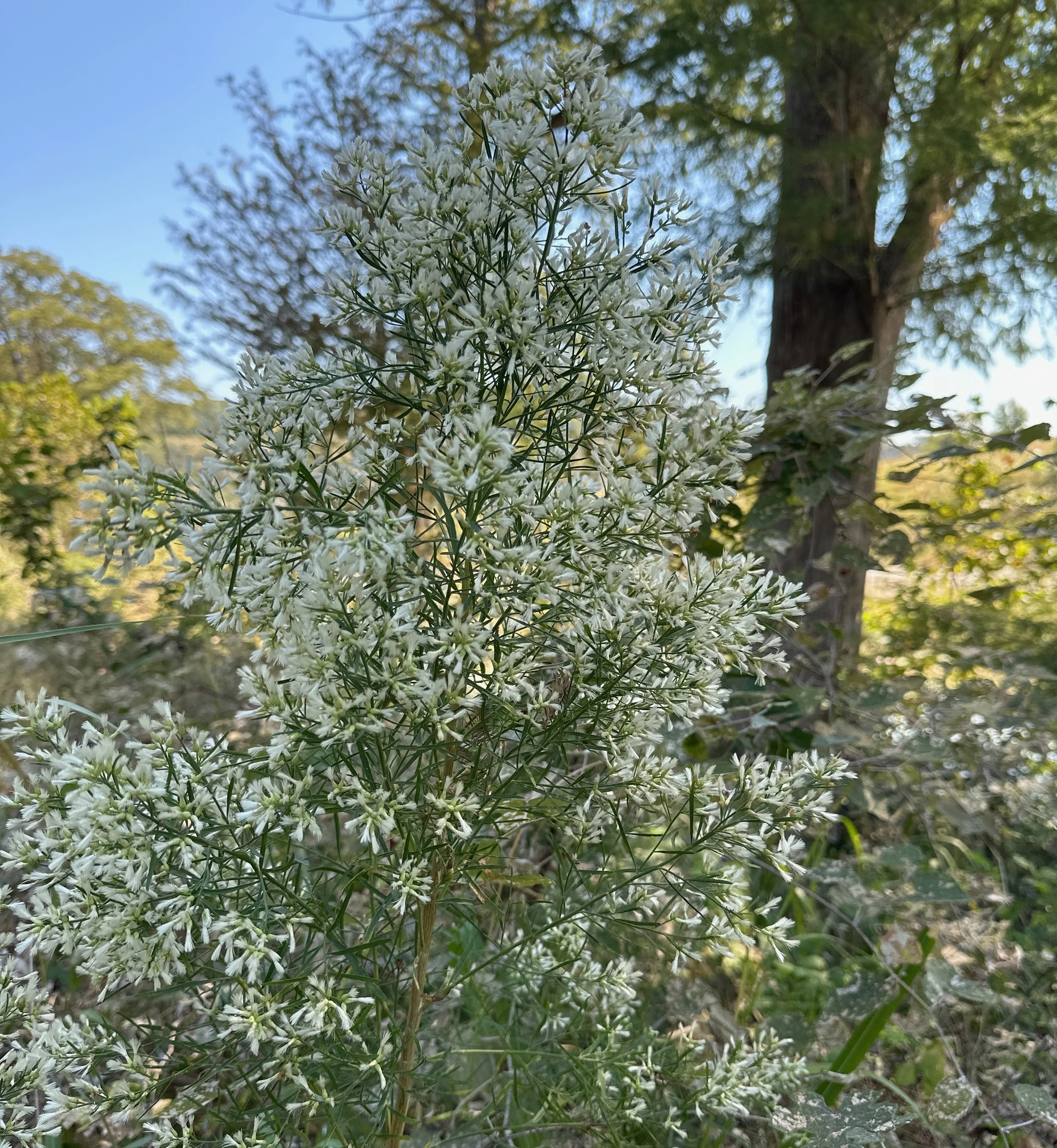

Baccharis—Filling the Void

A native with a 90+ year reputation for taking over is Roosevelt Weed (Baccharis neglecta). As its scientific name implies, Baccharis loves neglected areas—abandoned agricultural fields, degraded roadsides, and other plots of ground whose ecosystems we have somehow altered. The common names Roosevelt Weed, Poverty Weed, and New Deal Weed come from the 1930s Dust Bowl years, when Baccharis was intentionally planted in abandoned agricultural fields to stem the soil’s blowing across the United States.

Photo courtesy Christine Middleton

Baccharis was effective in stemming erosion—perhaps too effective, as it often became a monoculture. Agricultural fields can be particularly difficult places for ecological restoration. Farmers historically considered a wide variety of native species as weeds and worked to eradicate them, depleting the native seedbank. Baccharis produces a large quantity of seeds that are easily dispersed by the wind. Thus, if only Baccharis is planted—or if its seeds are the first to blow in—it can gain an outsized edge over other early succession species. Baccharis not only tolerates harsh conditions, it grows rapidly, especially in the full sun associated with abandoned agricultural fields. Thick stands quickly form, shading out potential competitors. And after being cut or burned, Baccharis resprouts easily, making control very difficult.

But wait before you judge this scrubby-looking shrub too harshly! In Lessons from Leopold, Steve Nelle observes that in riparian areas, “Baccharis is like a scab on a flesh wound—an important step in the healing process of scoured gravel bars.”

After a flood, it is often the first plant to take hold on newly formed gravel bars. In subsequent floods, it slows the velocity of water, reducing further erosion. It catches leaf and twig debris, which help build rich soil that enables important riparian species like switchgrass and sycamores to take hold. Baccharis does not like the moister conditions it helps create and gradually dies out.

Baccharis is of little or no value as forage for either cattle or deer—another factor in its favor. Its minute seeds are also of little value to either game or songbirds. However, its profusion of white fall flowers is a boon for pollinators of all kinds, and its blooms are particularly important as a nectar source for migrating Monarch butterflies. Thus, while management of Baccharis may be needed in upland areas where it has become dominant, any measures should also consider its value for pollinators.

Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

Frostweed—A Shade-loving Colonizer

Both Prairie Tea and Baccharis have the potential to spread widely because they are prolific seed producers. While most plants produce seeds, some also spread through vegetative reproduction. Vegetative reproduction is a type of asexual reproduction where new plants are formed from parts (stems, roots, or leaves) of the original plant. If a species persists at a location through the vegetative reproduction of its individuals, it is considered a clonal colony.

Frostweed (Verbesina virginica) is an example of one of our native species prone to form clonal colonies. Frostweed spreads via underground stems called rhizomes, which grow horizontally and send up new shoots, creating genetically identical plants. It also spreads via seeds dispersed by wind or animals. Frostweed loves shade and is highly deer-resistant.

Photo courtesy Christine Middleton

Other shade-loving plants tend to be less deer-resistant. Thus, when other shade species are under stress from herbivory, Frostweed can form dense thickets—leading some to curse its existence. But Frostweed has many redeeming qualities that extend beyond the neat trick it performs during a prolonged winter freeze.

Photo courtesy Christine Middleton

For more information on this phenomenon see Central Texas Frostweed in the February 2024 Hays Humm by Mike Meves.

Frostweed blooms attract a diversity of pollinators, including bees, butterflies, moths, and other beneficial insects. Like Baccharis, Frostweed is particularly important because it blooms late into the fall when other nectar sources are scarce. This means it provides critical food for bees preparing for winter hibernation. And as Monarch butterflies wing their way back to Mexico, the big white flower clusters provide a much-needed nectar snack as these dwindling butterflies pass through Central Texas.

Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

Frostweed’s expansion is naturally limited by its intolerance of sunny locales. But if Frostweed has formed more of a thicket under your trees than you find desirable, don’t be afraid to remove a few of the clones. Create smaller stands so other shade-loving natives can fill in the spaces. Consider adding more species to increase the diversity under your trees. Inland Seaoats (Chasmanthium latifolium) or, if the deer population permits, native Turk’s Cap (Malvaviscus arboreus var. drummondii) would be good choices.

Yaupon Holly—An Even Hardier Colonizer

Like Frostweed, Yaupon Holly (Ilex vomitoria) is prone to forming clonal colonies. It spreads somewhat differently—via root suckers. Multiple stems develop from a single root system, eventually forming a thicket that other plants, including tree saplings, find hard to penetrate. This tendency is accentuated when the main plant is cut or otherwise disturbed, complicating efforts to control it.

But that is only part of the story.

Yaupon has other natural competitive advantages.

The shrub does equally well in both full sun and full shade, grows in a wide range of soil types, is both heat- and cold-tolerant, and requires little moisture. Despite its drought tolerance, Yaupon can also survive in moist areas.

Historically, low-burning fires helped keep the spread of Yaupon under control, since Yaupon is fire-prone.

Photo courtesy Jack Downey

Deer and cattle will eat Yaupon’s leaves and tender stems, especially when little other nutritious food is available. Stiff, untouched branches protect inner leaves so that, even under heavy browsing, the shrub survives and spreads. Many other natives don’t.

Photo courtesy Christine Middleton

So, in cases where past abuse has contributed to Yaupon domination, some management may be necessary. But remember: simply cutting Yaupon can compound the problem. It’s best to immediately follow up by carefully painting the stumps with herbicide.

HELM Still Has Openings for Spring Visits

Want help identifying plants and better understanding their place on your property?

As part of the Hays County Master Naturalist project called HELM (Habitat Enhancing Land Management), we offer property visits to discuss land stewardship. Landowners learn about sustainable practices designed to enhance wildlife habitats, improve soil health, effectively manage invasive species, and much more.

Photo courtesy Christine Middleton

If you or your neighbors would like the HELM team to visit, simply fill out the request form at BeautifulHaysCounty.org. And please help us spread the word!

The HELM Network News is a periodic feature in The Hays Humm, an online magazine of the Hays County Chapter of Texas Master Naturalist™. The latest issue of the magazine, as well as articles from past issues, can be found at BeautifulHaysCounty.org.

Following publication, HELM Network News articles are also sent to a mailing list. You can sign up here to get the articles sent directly to your inbox.