Land Stewardship is for the Birds

Part 1 - What Do Birds Need?

Habitat Enhancing Land Management

Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

“Ok. It's possible that birds may sing just for the joy of it.”

—Kyo Maclear, Birds Art Life: A Year of Observation

Christine Middleton

Birds may or may not feel joy. Landowners who listen to them do! How can you make your little piece of the Texas Hill Country even more inviting for our feathery friends? Attracting birds to your property involves more than just putting up a bird feeder. According to David Allen Sibley’s What It’s Like to Be a Bird: What Birds Are Doing and Why, “Even chickadees, among the most dedicated bird feeder customers, get at least 50 percent of their food in the wild.”

Birds require healthy habitats in which to thrive and bring up the next generation. That definitely means sources of food beyond what humans provide. But wild food is just one part of the equation. Clean water for both drinking and bathing, places to hide from predators, and shelter during inclement weather are just as essential for survival. And to ensure continued presence, birds need safe havens in which to build their nests and raise their young.

Bird populations have declined dramatically since 1970—three billion and counting. These declines have not just impacted rare species. Recent research using eBird data showed that 75% of North American species are in decline. And habitat loss is considered a significant factor. Increased conversion of land to agriculture and large-scale development are often cited as destroyers of bird habitat. But the fragmentation and manicuring of Hill Country acreage also contribute. Whether you have a small backyard or several acres, you can help by understanding what birds need and what you can do to help.

What Do Birds Eat?

Yellow-rumped Warbler Eating Seeds Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

One of the most basic needs of all living creatures is food. Like us, birds don’t always eat the same thing. Resident birds need sustenance all year round while migrants need food sources timed to when they pass through Central Texas. And bird diets vary significantly by species. Those like finches who flock to feeders for an easy meal are granivores. Then there are insectivores like bluebirds who survive mainly on insects. Frugivores like waxwings and robins spend the winter wandering around Texas in search of juniper berries and other fruits. And don’t forget nectarivores like hummingbirds and carnivores like hawks.

Golden-fronted Woodpecker Eating Possumhaw Berries Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

Summer Tanager Consuming an Insect Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

There are also omnivores like blue jays who eat lots of different things—acorns, seeds, insects and even small vertebra like mice. However, most birds shift their diet, often seasonally, based on what is available or as a supplement to normal dietary preferences. Lesser Goldfinches will eat flowers, tree buds, and some berries. Both finches and bluebirds eat fruit in winter when seeds and bugs are scarce—not just juniper berries, but other berries like mistletoe, sumac, and hackberry. Robins and cedar waxwings will eat insects when they are available. Hummingbirds also eat small insects and spiders.

Lesser Goldfinch feeding on Mealy Blue Sage Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

And, no matter what they eat as adults, 96% of terrestrial bird species feed their nestlings bugs. In his book Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard, Doug Tallamy observes that caterpillars are a much-preferred bird baby food because of their relative size. He asks, “If you were a bird looking for insects, would you choose to hunt and handle 200 aphids, or would you seek out a single caterpillar to feed your babies?” It has been estimated that a single clutch of chickadees requires 5,000 caterpillars before they fledge. But don’t forget that bird menus also include other kinds of bugs such as flies, beetles, and crickets, as well as spiders.

Canyon Wren Feeding an Insect to a Fledgling Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

Birds also use a wide variety of plant materials to build their nests—most commonly sticks, dry or fresh leaves, grasses, and bark.

Black-capped Vireo Constructing its Nest Photo courtesy Tom Hausler

Golden-cheeked Warblers famously rely on strips of bark from old-growth cedar. To keep their nestlings comfortable, birds often line their nests with feathers, moss, fluffy seed heads, or hair. Titmice have been observed pulling hair from dogs or humans to provide their babies with more comfort. Birds also use a variety of materials to hold their nests together and hide them from predators. Vines or other plant material, as well as spider webs, are frequent choices. Hummers attach lichen to the outside surface of their nests as camouflage.

Black-chinned Hummingbird video courtesy Betsy Cross

Water is Critical

Like all animals, birds need water to aid digestion and improve blood circulation. Birds lose water through their droppings, respiration, and evaporation. The biology of songbirds means they lose more water than other bird species. Frugivores and insectivores have an easier time because the fruit and insects they consume provide moisture. But seeds are dry, so granivores definitely need a supplementary source of water. And all birds need lots of extra water during periods of extreme heat. For more on why birds need water, see this earlier Hays Humm article by Tom Hausler: Water! Water! Water! The Importance of Water for Birds.

One experiment with house finches found that at 68 degrees, the birds drank an average of 22% of their body weight in a day. At 102 degrees, they needed more than twice that amount. Like dogs, birds don’t sweat. That’s why on a hot summer day you might see a bird panting. What panting birds are doing as they open their bills wide and expand their throat is exposing moist skin. The birds then breathe at about three times their normal rate, causing the water to evaporate and cool them down. But that also means they need a source nearby for replenishing all that lost water.

Titmouse Panting to Cool Off Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

And have you ever watched birds splashing around in a bird bath or shallow puddle? Birds spend a lot of time preening their feathers, and bathing appears to be an important part of this ritual. Bathing helps remove dirt, oils, and parasites and realign feathers to maximize flight efficiency. Feathers are replaced just once or twice a year. Thus, maintaining them in top condition is crucial to survival, particularly when speed is key to escaping predators.

Painted Bunting Enjoying a Bath Photo courtesy Mike Davis

An Eastern Bluebird, 2 House Finches, 2 Lesser Goldfinches, and a House Sparrow (November 1) Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

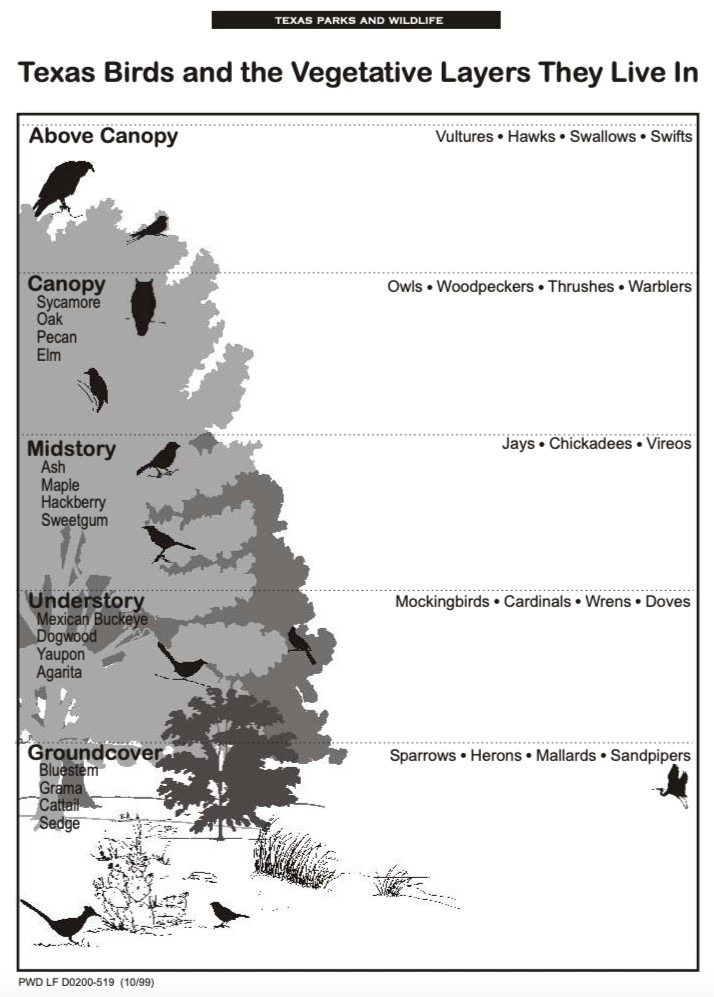

Survival Requires Safe Places

Birds also need safe places to build nests and raise the next generation. Like food, birds don’t like the same things. Many birds nest in trees and shrubs, while others choose the ground. Preferences are often related to how they feed (e.g., ground feeders vs. aerial insectivores). Meadowlarks build sometimes elaborate nests on the ground using grass, stems, and bark. Cardinals wedge their nests in the fork of a small branch or within a tangle of vines—usually 1–15 feet off the ground. Painted buntings pick spots to hide their nests in dense foliage, usually a location 3–6 feet off the ground. And hawks are among those who quite logically raise their young in the canopy.

Eastern Phoebe Nest with Fledglings under the Porch Photo courtesy Betsy Cross

Then there are the cavity nesters who prefer holes in trees. Cavity nesters can be further divided between primary cavity nesters like woodpeckers, who create their own holes, and those that simply look for holes that either occur naturally or were created by primary cavity nesters. These secondary cavity nesters are being impacted by both declining woodpecker populations and the human tendency to remove dead trees. But such birds will also use properly constructed birdhouses—not a bad idea for landowners wanting to encourage secondary cavity nesters such as bluebirds, chickadees, titmice, and wrens. See more about cavity nesting birds in this November 2022 Hays Humm article by Betsy Cross: For the Love of Nesting Birds—Observations from the Field.

Escaping predators involves more than just flying away. During and outside the breeding cycle, adult birds also need adequate cover. Short grass and tall trees just don’t hack it. Many birds like to forage at the “edge,” where grasslands meet woodlands. Oak/juniper mottes dotting grassland savannah are great places for emergency shelter. So are human-provided brush piles and rock piles. And even outside the breeding season, cavity nesters will use tree holes or nest boxes when threatened.

These same thicketed places provide birds shelter from inclement weather. Did you know that birds can sense barometric pressure? When the pressure drops, birds instinctively know a storm is on its way. The first thing they do is eat frantically. Have you ever noticed birds flocking to your bird feeder just before it starts to rain? With enough food in their bellies, the next thing they do is find the best shelter they can to sit out the storm.

What Does Good Bird Habitat Look Like?

There’s not just one simple answer to that question. First of all, individual bird species are attracted to different kinds of habitats. Here are just a few examples:

Golden-cheeked Warblers rely on mature, mixed Ashe juniper (cedar) and oak woodlands.

Savannah Sparrows like open grasslands with few trees.

Eastern Bluebirds need grasslands that are adjacent to wooded areas.

And, just like birds, Hill Country properties differ greatly in terms of what kind of habitat they can support. Some are hilly and covered with trees. Others are flat with lots of grass, but few trees. Larger properties may have a little of both. Plant communities vary based on the combined influence of factors like slope of a property, what direction that slope faces, soil type and depth, and underlying geology. And those plant communities will influence what kind of birds decide to visit. Even small backyards can be landscaped in ways conducive to healthy bird habitat.

So the first question a landowner whose goal is to attract more birds should ask is, “What kind of habitat or habitats can my particular property support?” In their book Attracting Birds in the Texas Hill Country: A Guide to Land Stewardship, the authors, W. Rufus Stephens and Jan Wrede, discuss six upland plant communities, of which two are commonly found on properties visited by the HELM team—Mixed Wooded Slopes and Live Oak Savannas.

Mixed Wooded Slopes are characterized by a nearly closed canopy with a diverse mix of trees of various ages, short- to medium-height ground cover, and a well-developed understory. The slope and aspect (i.e., the direction in which the slope is facing) will influence what plants grow on that slope, which will in turn influence what birds gravitate there. Moister north, east, and northeast slopes will have more plant diversity. More drought-tolerant plant species will inhabit hotter, drier south, west, and southwestern slopes.

Live Oak Savannas are flatter, wildflower-rich grassy areas dotted with clumps of live oaks. But this doesn’t mean the “park-like” version often seen—tall trees and mown grasses. The dominant grasses are taller, warm-season natives like Little Bluestem and Yellow Indiangrass. Among these bunch grasses are open spaces, leaving room for a diversity of wildflowers. And the tall trees do not stand alone. Rather, they grow in mottes that also include lots of other woody trees and shrubs.

Unfortunately, many of the properties HELM visits have suffered years of abuse, much of which happened long before the current owners bought the property. The damage started over 100 years ago. Cedar choppers removed “old-growth” Ashe junipers. Ranchers brought in non-native pasture grasses, selectively destroyed native vegetation considered toxic to livestock, and often kept stocking rates too high. Over time, undesirable non-native species—both plants and animals—invaded the Hill Country. More recently, deer populations have exploded in ways that are detrimental to native shrubs, trees, and forbs.

All this abuse has shifted plant communities in ways that have altered the natural composition, structure, and diversity of good bird habitat. Where land has been overgrazed, ground cover is sparse. Diverse oak mottes have been altered in ways that lessen their value as habitat. In wooded areas, goats and deer have created a browse line, reducing the availability of woody understory. Excessive cedar clearing on slopes has resulted in loss of valuable soil. And groundwater depletion means fewer properties provide springs, seeps, and other natural water sources.

Lessons HELM Has Learned

In addition to visiting properties around Hays County, members of the HELM team are working hard to make our properties more inviting to birds and other wildlife. Some of us own small suburban lots, while others are blessed with more Hays County acreage. Over the years, we have done a lot of experimentation and observation. We’ve had our share of of successes and missteps and love to share what we’ve learned. Here’s just a taste of what HELM team members have done.

Let’s start with food. Many small properties like mine are food deserts—lots of exotic species that don’t produce edible seeds or fruits and don’t attract insects. Since moving to San Marcos a year and a half ago, I have been in the process of correcting that by replacing builder-provided non-native species with natives. One of my early successes was the Maximilian Sunflower (Helianthus maximiliani) I planted by my bedroom window. After seeds began to develop on the spent flowers, I looked out and saw goldfinches perched on the stalks, chomping down. What an unanticipated delight!

Maximilian Sunflower Photo courtesy Christine Middleton

Years ago on a larger property, Cathy Ramsey planted a small D-pack of Texas Cupgrass (Eriochloa sericea). It spread rapidly. Range ecologists call cupgrass an “ice cream plant” because grazers consume it with relish. As a result, cupgrass has become extremely rare in our area. Ever observant and eager to share her observations, Cathy noticed Painted Buntings eating cupgrass seeds almost every time she looked. She sent Native American Seed an e-mail. They noticed the same thing happening in their planted rows of cupgrass. Soon, with each new issue of their catalog, pictures of buntings consuming cupgrass became more and more prominent.

Painted Buntings eating cupgrass seeds. Photos Native American Seed with permission

Water is something the HELM team often finds missing on properties we visit. Providing water for birds can be as simple as a well-maintained shallow dish or birdbath, as I have done on my small property. But other HELM team members have gone above and beyond. Of particular note are Tina and Bob Adkins, who recently converted an aging, infrequently used swimming pool into a triple-waterfall stream.

Around the border, Tina and Bob planted lots of native plants and sowed native turf grass across the rest of the area.

Photos courtesy Tina Adkins

Tina reports, “The bubbling stream has brought a tremendous amount of wildlife and peaceful time for us at the end of the day.”

Another member of the HELM team, Maggie Carpenter, created a water feature using a stock tank combined with an elevated rock-filled dish and a pump for recirculating the water. In another part of her yard, a simple ground-level dish kept filled with fresh water also attracts birds and other wildlife. Maggie also created mid-story habitat behind her tank by letting yaupon and flame-sumac grow back after her builder razed everything but oaks and a few Ashe junipers. Maggie suggests, “Water is even better at attracting birds than feeders, and watching birds bathe is great entertainment!”

Photos courtesy Maggie Carpenter

Stock tank with aquatic plants and rock-filled dish for birds

Summer Tanager (upper right) and Cardinal ( in the rock-filled dish)

Painted Bunting and Lesser Goldfinches

Indigo Bunting

Maggie’s twin sister, Cathy Ramsey, reminded us to make sure there are no easy hiding places for predators near feeders or water features. She found that the galvanized water trough she had provided quickly became a “predator magnet” because of an Ashe juniper positioned at one end. Given sufficient cover, one particular feral cat became expert at picking off young turkey poults when they came to drink. She observed, “One mother was incredibly fierce, and all of her young made it, but other mothers were less attentive and repeatedly lost young.”

Lots more to tell. But that needs to wait till Part 2, which will focus on assessing your property and developing a plan for improving bird habitat. Or, if you own acreage in Hays County, we’d love to come and talk to you directly about what you might do. As part of our HELM (Habitat Enhancing Land Management) program, we offer property visits where landowners can learn about sustainable practices designed to enhance wildlife habitats, improve soil, effectively manage invasive species, and much more!

We are currently taking requests for Spring 2026 visits. If you would like to schedule a HELM visit, fill out this form. And please help us by spreading the word to your friends and neighbors.

The HELM Network News is a periodic feature in The Hays Humm, the online magazine of the Hays County Chapter of the Texas Master Naturalist™. You can read the latest issue and explore past articles at this link.